The breeding season is nearly year-long, extending from mid December to the following November. In Oregon, the breeding season begins in late December or early January, and there are three peaks in breeding activity: January to February, mid April to early May, and October to mid November. Preliminary data from Malcolm McAdie's research indicate that breeding occurs between mid February and mid June on Hornby Island, with two possible peaks in breeding. No breeding Opossums were found on Hornby in the fall. Although it appears that females breed throughout the year in Oregon, most authorities have concluded that females can produce only two litters in a breeding season. From one to seventeen young may be born, but the litter size is usually six to ten. Malcolm McAdie observed litter sizes of one to twelve, with seven most common, for the Hornby Island population. Litters of one young are probably unsuccessful because the stimulus of at least two nursing young is needed to maintain lactation.

The gestation period is only 13 days. The tiny newborns, weighing only 0.13 grams and measuring about 14 millimetres in length, immediately crawl to the pouch with no assistance from the mother. The front feet of the newborn are well developed and are equipped with deciduous claws that help it crawl to the pouch. Once inside the pouch, a young Opossum attaches itself to a nipple. Within a few days the tip of the nipple enlarges inside the mouth and the young is firmly attached to its mother where it will nurse for 55 to 60 days. By 55 days the eyes and mouth begin to open, and short sparse hair is evident. At 70 days the young begin to make short trips outside the pouch, and they may be left in the den when the mother forages. They are weaned and become independent of their mother at around 100 days of age. Although the mother provides milk and protection, maternal behaviour is poorly developed. Males play no role in the raising of the young.

Captive female North American Opossums may breed at six months and males may reach sexual maturity by eight months. Fertility is reduced in older females, and most of the breeding animals in a population are those that were born the previous spring.

|

Numerous studies of food habits in the midwestern and eastern states have demonstrated that the North American Opossum is an opportunistic feeder that preys on a variety of vertebrate animals and scavenges carrion and garbage. Major prey are small mammals, birds, amphibians, reptiles, earthworms, snails, insects, fruits and other plant material. Dietary data for Pacific coast habitats are limited to David Hopkins and Richard Forbes' study of an urban opossum population in Portland, Oregon. Hopkins and Forbes found that small mammals, earthworms, slugs, beetles, pet food, fruits, grasses and leaf litter were the most important foods for this population. The relative importance of these food types varied seasonally: mammals were the most important in winter and spring, slugs in summer, and fruits in autumn. More than half the mammals in the opossums' diet were North American Opossums, presumably carrion from road kills. Few birds, reptiles and amphibians were eaten by the Portland population. Birds seldom represent more than seven per cent of an opossum's diet; the reputation of this mammal as a major predator of bird eggs and nestlings may be exaggerated. In some parts of eastern North America, frogs, toads, salamanders and snakes are important food items. Their low occurrence in the Portland study may reflect low populations in an urban setting.

|

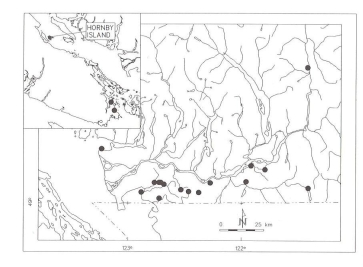

Movements and home range size have been studied by live-trapping and radiotelemetry. There is no evidence that the North American Opossum is territorial: home ranges of adults and juveniles of both sexes seem to overlap extensively, and individuals may share the same den site. Home range estimates are from 5 to 39 hectares. Males tend to have larger home ranges than females, and home range size is larger in unproductive habitats such as intensively cultivated farm land. Adults generally travel 300 to 600 metres from their dens when foraging at night. The young usually remain close to the den, but when they disperse they may move long distances covering several kilometres in a single night. Females with young may be loyal to the same den site, especially during the weaning period, but non-breeding females and males change their den sites often. For example, a male followed by radio tracking used 19 different dens in five months. Population densities generally range from one to five animals per square kilometre, but in some habitats populations can reach a hundred opossums per square kilometre.

The North American Opossum is active between dawn and dusk. It does not hibernate, but it is less active in the winter; more daytime activity is evident during cold spells. Opossums accumulate some fat stores for winter, but their fur does not provide much insulation. They fill their dens with dried leaves and grass to form well-insulated nests. When the temperature falls below freezing, opossums deal with the cold by remaining in their dens and reducing the temperature of poorly insulated extremities such as the ears and tail. The northern limits of the North American Opossum are determined by winter temperature. Animals living at the northern edge of the range, including coastal British Columbia, often have frostbite damage on their ears and tails.

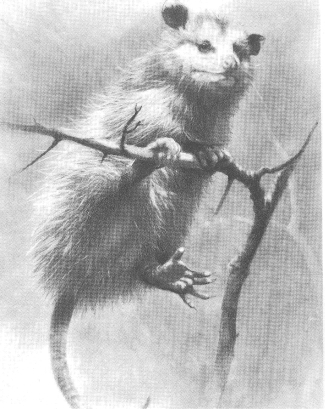

The North American Opossum walks on the soles of its feet. It is a slow but capable climber, using hand-over-hand movements; the opposable "thumb", prehensile tail and friction pads on the feet provide a firm grip on branches. It transports nesting material in its coiled tail, and uses its front limbs and mouth to construct the nest. Opossums are unable to dig burrows, but exploit ground dens constructed by other mammals. They will readily enter water and are capable of swimming distances of several hundred metres.

North American Opossums are solitary. Males tend to be aggressive to other males, and their encounters are characterized by open-mouth threats, growling and screeching. They use various dance displays and bluffing routines to establish dominance. If neither male retreats, the encounter may escalate to a fight to the death.

The opossum will employ any of several defence behaviours when it encounters a potential predator. The best known is "playing possum", feigning death: the opossum falls on its side, body flexed and immobile, mouth slightly open and emitting large amounts of saliva; it usually recovers immediately after the threat is over.

North American Opossums seem to have short life spans: most do not survive beyond one breeding season. Captive animals may live for four years, but in the wild, few live beyond two years. Survival rates are low. Only 25 to 40 per cent of the young survive the first four weeks after weaning and as few as 10 per cent survive to their first breeding season. Their predators include Coyotes, Bobcats, Racoons, Red Foxes, dogs and Great Horned Owls. Motor vehicles take a large toll on the opossum, and road kills are a common sight along highways in the Fraser River valley.

|

|